Repost: Build Your Own Record

Edited from Rao Yi Science WeChat Official Account

When you are young, it is very important to build a good record.

For older people, it is hard for others to misunderstand them because there are many records. If someone tries to spread rumors, they will not succeed because you have records. If someone criticizes you for shortcomings in some areas, you have records to refute or show your strengths in other aspects.

The younger you are and the less experience you have, the more important it is to build your record.

Graduate school is your first step into a semi-professional state. There are still exams, but they are less important. What matters more is your record.

Your record is the career and life you gradually accumulate.

How do you leave a record?

-

Use a scientific notebook to record your scientific ideas, experimental designs, results, analyses, research conclusions, including repeatedly recording your mistakes and the process of correcting them, etc. Decades later, you can look back in your notebook and see how you grew from an enthusiastic and naive graduate student, often needing help, to an independent and mature scientist.

-

Leave a record of yourself in others’ minds through your words and actions. Whether you are passionate and insightful about science, whether you are warm and friendly to classmates, whether you can build scientific communication with teachers… Your classmates, colleagues, and teachers all have records of you. Even having no impression is a kind of record.

Decades later, people will still evaluate and recall you based on their memory of you.

When it comes to keeping records, the most worthy of your learning is the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, which started from Jiangxi.

From 1927 to 1934, few could foresee the Red Army’s future success. Outside Jiangxi, there were many warlords with their own territories, and the Red Army’s material resources were far inferior to those of some warlords. But the Red Army had lofty ideals, a national organization, and great confidence.

In 1934, the Red Army was forced to leave Jiangxi and began what would later be called the Long March. They could not carry much, only strategic necessities. Among the items they considered indispensable, there was something special: the telegrams exchanged among themselves.

After reading the telegrams and confirming the information, why not discard them to lighten the load? Why not carry more food, guns, or bullets, or simply reduce the burden of the march?

They said, “We need to check the telegrams in the future and look at history.”

Few in the Red Army were over thirty; most were in their twenties or even younger. On the Long March, those lacking ideals or confidence would leave the ranks. But among these young people, some had great self-esteem and confidence, believing they were creating Chinese history.

They kept the telegrams because they were confident about their future, even in dire circumstances.

History proved that these young Red Army members, who valued their records and preserved them well, created Chinese history and influenced world history.

I hope young students will build their own records and leave records in others’ minds through their scientific notebooks and actions.

Appendix: August 2, 2021

I have always advised students to keep records, not for others, but for themselves: the person who cares most about your history can only be yourself.

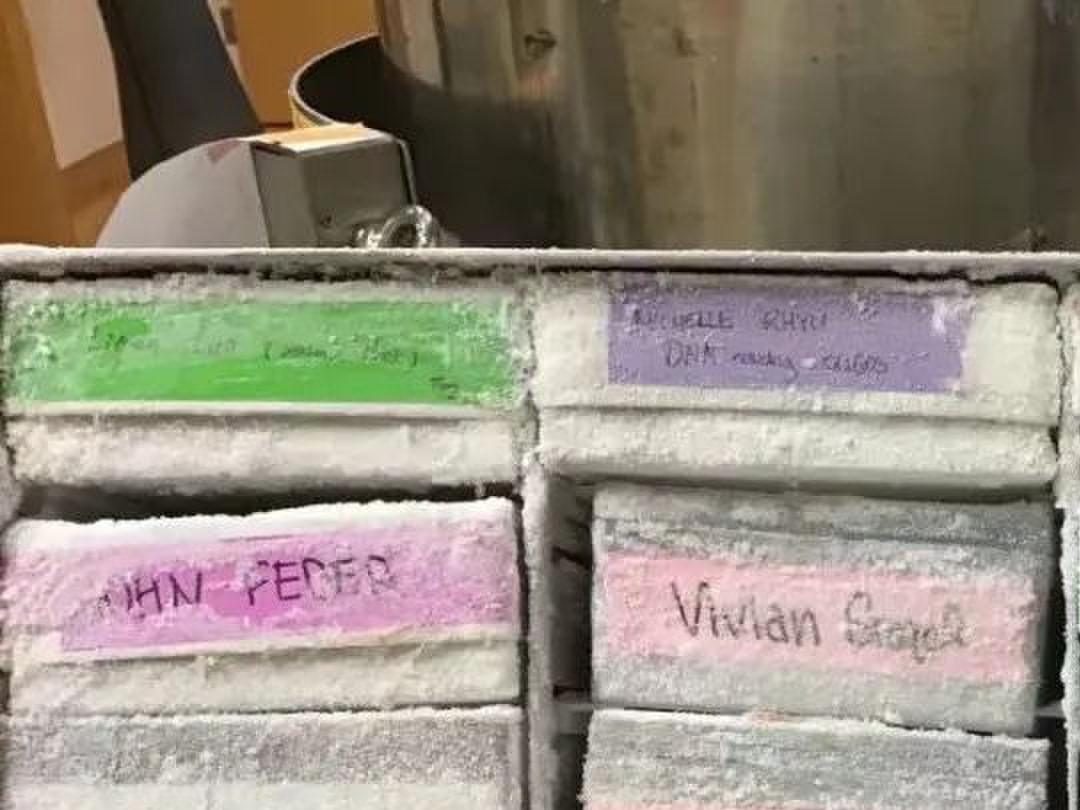

Recently, I saw a photo from the Jan Lab at UCSF, where I did my graduate studies. In the lab fridge, there are experimental supplies from people who used to work there. There is a box labeled with my name, 1991 (the year I left).

I guess it is DNA. At that time, DNA was precious. Cloning a gene was the main work of my six years as a graduate student in the US (before that, I had two years of graduate study in Shanghai, and I never felt the eight years were long).

Even today, this kind of gene cloning cannot be done simply by PCR. It requires finding the mutated DNA based on the phenotype of fruit flies. After obtaining it, you reintroduce the normal DNA into the mutant flies to rescue them. The whole process is similar to finding the mutated DNA in a patient, then reintroducing normal DNA into the patient for gene therapy, proving that this DNA segment indeed carries the gene causally related to the disease (this is the category; at that time, it could not be done in humans, but could be done in fruit flies).

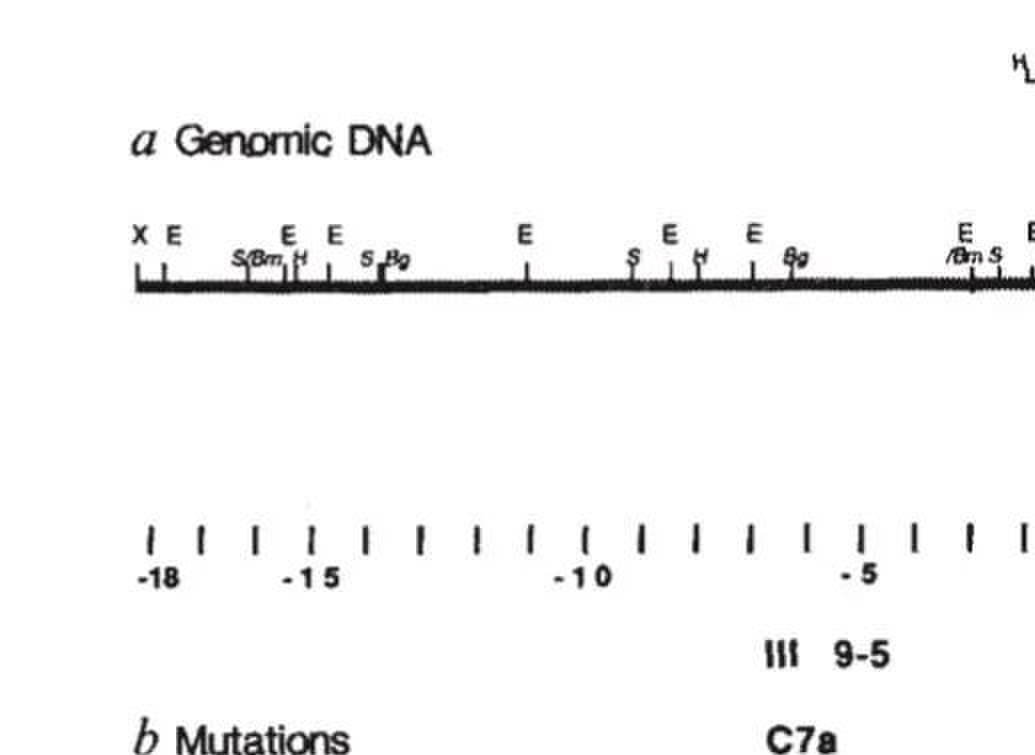

This shows a segment of DNA, two independent transposon insertions causing mutations, and three small deletion mutations. PWB is the fragment used for “gene therapy”, introduced into fruit flies via transposons, and proved to rescue the mutant phenotype.

Thinking about it, in the 1980s, there were probably fewer than ten Chinese students who completed the entire process from gene cloning to gene reintroduction for “gene therapy” in lower animals. At that time, in higher animals (mice, humans), people usually only did half (either gene cloning or transgenics). Researchers working on human gene therapy generally did not do gene cloning, and those who did gene cloning generally did not do gene therapy. Because both steps were troublesome, most people only did one.

For those studying lower animals like fruit flies and nematodes, we did both steps.

But at that time, there were only a handful of Chinese students working on fruit flies and nematodes, and those who completed the whole process were among them. Of course, today’s gene therapy methods for humans are different from those for fruit flies, but the concept is the same, and the technical principles are the same, only the vectors and genes differ.

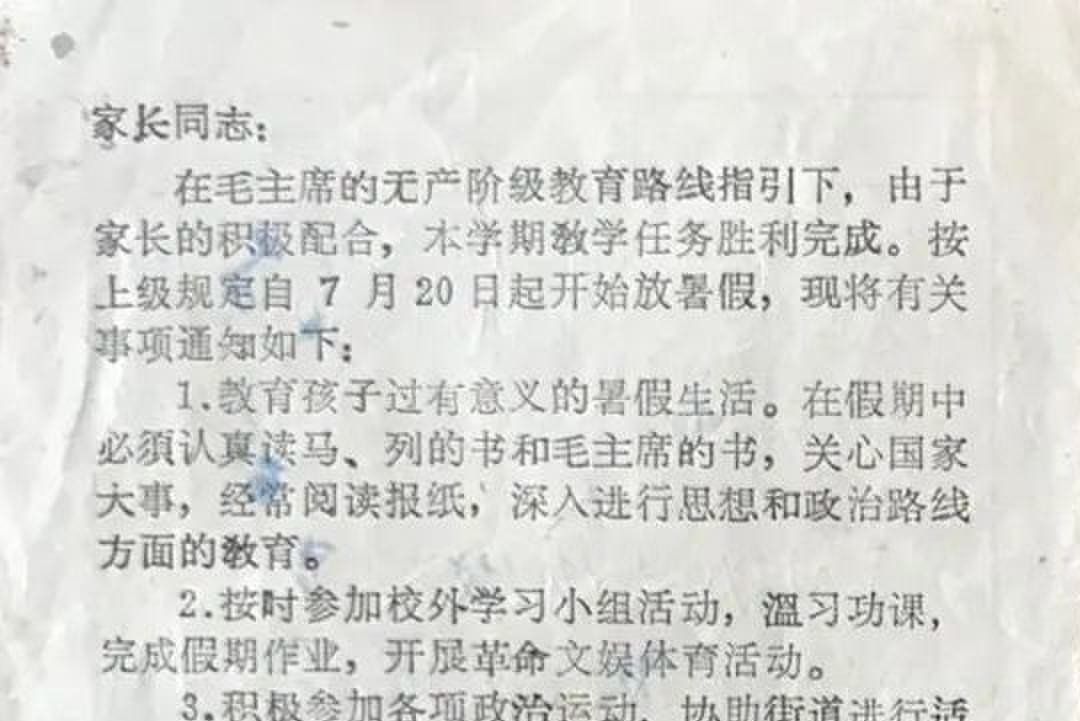

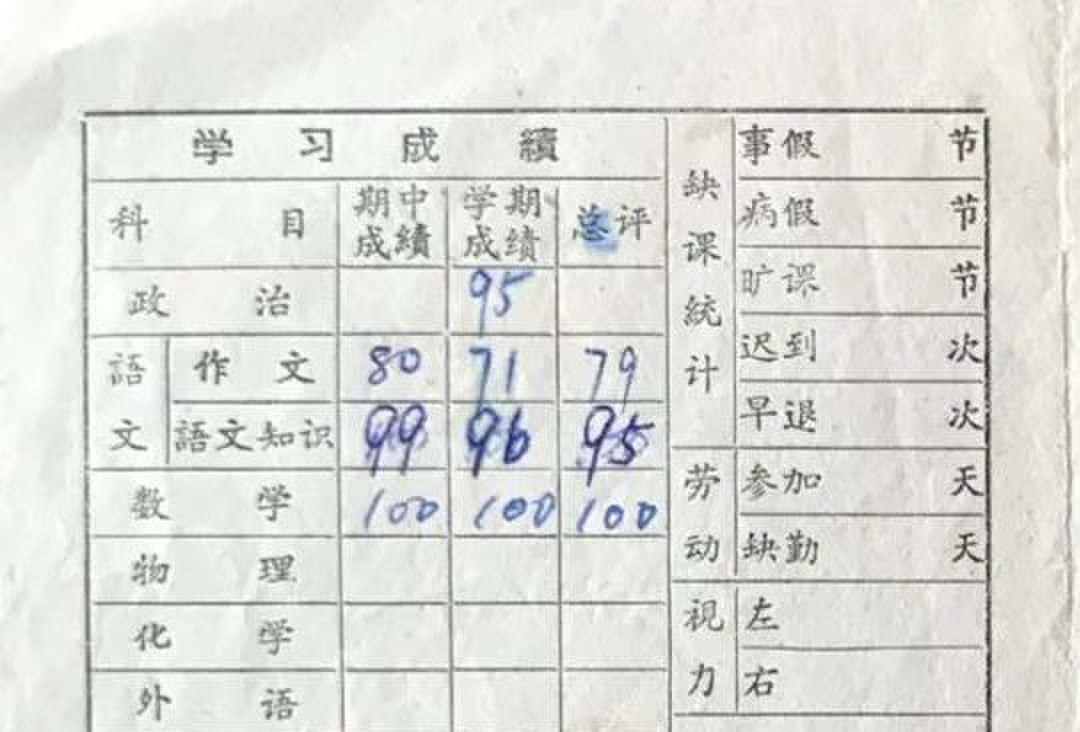

It is not easy to keep a complete record. I may have all my transcripts. I transferred to Nanchang from a commune (Liugongmiao, Qingjiang County, now possibly called Liugongmiao, Zhangshu City) where my parents were sent down, in the last semester of fourth grade in elementary school. After that, I had transcripts. Maybe there were no transcripts in the countryside, only some kind of report. The early transcripts were probably kept by my mother. Later, I may have kept them myself, so I have transcripts all the way to graduate school in the US.

When moving in the past, I mainly took important items with me.

Unfortunately, after returning to Peking University, I moved five labs in fourteen years, and eventually things got lost.

When I returned to China in 2007, the lab Peking University gave me was very small (lab space plus office was 60 square meters), so I had to continue using the lab at the Beijing Institute of Life Sciences. For faculty recruitment at Peking University, I could not reveal the space limitation at that time and had to solve it gradually.

For several years, I commuted daily (usually working at Peking University in the morning and at the Institute in the afternoon). After a few years at Peking University, I had a lab of over 100 square meters, but the two rooms were at opposite ends of the corridor, and one was next to the restroom, which was not ideal for work.

After stepping down as dean, the space improved, first with a new comprehensive research building, then the Wang Kezhen Building. After moving to the Wang Kezhen Building, the lab space was finally sufficient.

I put in a lot of effort and used various methods to expand the life sciences space at the main campus of Peking University. One method was to distribute the space in different places, not all in the School of Life Sciences, because if all the space was in the School, it would be hard to get repeated support from the university.

The biggest achievement in terms of space was the construction of the new Life Sciences Research Building (later named the Lui Che Woo Building). In 2009, the university approved it, and after various processes, on April 12, 2019, my own lab also moved into the new building, completely solving the space problem.

Because this was after the space issue for the School/Discipline of Life Sciences was resolved, I call it “the joy after the joy of life sciences”.

It is possible that my office now has the best view in all of Peking University.

This is today’s record, a good time for summer research.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: